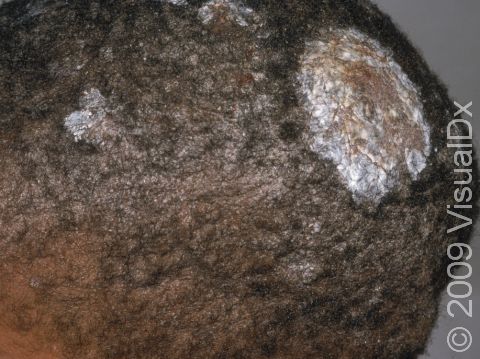

Ringworm, Scalp (Tinea Capitis)

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp, commonly known as scalp ringworm, which is caused by a fungus called Trichophyton tonsurans. In a typical infection, the hair follicle becomes infected, and a small red lesion appears. This can spread outward in all directions, causing a large, scaly, circular lesion. The hair that is involved usually becomes brittle and broken, and the affected area is extremely itchy. If the scalp ringworm is left untreated, the scalp can become soft and very tender (boggy) as the infection spreads throughout the body. Children with scalp ringworm may have fever and pain along with enlarged lymph nodes.

Who's At Risk?

Black and Hispanic children are at higher risk for scalp ringworm than other populations. Although the typical age that children become infected is between 3–7 years, infants can become infected, especially if other members of the household have a ringworm infection. Spores from the fungus may be airborne and spread easily. Direct contact through sharing of combs, hats, etc also spreads the spores of the fungus; the spores can be present on furniture as well, which facilitates transfer of the fungus.

Signs & Symptoms

The most common locations for scalp ringworm include:

- Scalp

- Eyebrow (rare)

- Eyelashes (very rare)

Scalp ringworm appears as one or more round to oval areas covered with gray sheets of skin (scale) and is often accompanied by hair loss. The patches may be red and inflamed, and small pus-filled bumps (pustules) may appear. Also, tiny black dots may appear on the surface of the scalp, consisting of broken hairs.

Certain areas (lymph nodes) at the back of the scalp, behind the ears, or along the sides of the neck may be swollen.

One complication of scalp ringworm is a kerion, a large, oozing, pus-filled lump. If not treated aggressively, a kerion can lead to scarring and permanent hair loss.

Scalp ringworm is usually itchy.

Self-Care Guidelines

There are no effective self-care measures to treat scalp ringworm.

To prevent scalp ringworm:

- Have your child avoid close contact with infected people and pets.

- Teach your children about the dangers of sharing combs, brushes, hats, and hair accessories with friends.

Treatments

To confirm the diagnosis of scalp ringworm, the physician might scrape some surface skin scales onto a slide and examine them under a microscope. This procedure, called a KOH (potassium hydroxide) preparation, allows the doctor to look for tell-tale signs of fungal infection.

Sometimes the doctor will also perform a culture in order to document the presence of fungus or to discover the particular fungus that is causing the scalp ringworm. The procedure involves:

- Plucking a few hairs from involved areas of the scalp

- Rubbing a sterile cotton-tipped applicator across the skin to collect scale and any pus

- Sending the specimen away to a laboratory

Typically, the laboratory will have results within 2–3 weeks. Sometimes the laboratory is able to identify the type of dermatophyte that is causing the scalp ringworm.

Occasionally, a Wood’s lamp is used to look for the fungus. In this procedure, the doctor shines a black light at the scalp, and certain strains of dermatophyte may appear as fluorescent yellow-green spots.

Scalp ringworm is treated with oral antifungal medicines because the fungus invades deep into the hair follicle, where topical creams and lotions cannot penetrate. Scalp ringworm usually requires at least 6–8 weeks of treatment with oral antifungal pills or syrup, including:

- Griseofulvin

- Terbinafine

- Itraconazole

- Fluconazole

- Ketoconazole

Often, the doctor will also prescribe a medicated shampoo to reduce the risk of spreading the infection to someone else:

- Selenium sulfide shampoo

- Ketoconazole shampoo

Occasionally, untreated scalp ringworm seems to heal on its own when a child reaches puberty.

Visit Urgency

See your child’s doctor or a dermatologist if your child has hair loss or itchy, scaly spots on the scalp.

If a close contact of your child (sibling or classmate) is diagnosed with scalp ringworm, make sure you examine your child’s scalp, looking for scaly spots. If you are suspicious about an area, take the child to see a doctor for an examination.

If your child is diagnosed with scalp ringworm, have any household pets evaluated by a veterinarian to make sure that they do not also have a dermatophyte infection. If the veterinarian discovers an infection, be sure to have the animal treated.

References

Bolognia, Jean L., ed. Dermatology, pp.1174-1185. New York: Mosby, 2003.

Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. pp.645-646, 1993-1995, 2443-2446. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

Last modified on August 16th, 2022 at 2:44 pm

Not sure what to look for?

Try our new Rash and Skin Condition Finder