Bedsores (Pressure Ulcers)

Bedsores (pressure ulcers), also known as pressure sores or decubitus ulcers, result from prolonged pressure that cuts off the blood supply to the skin, causing the skin and other tissue to die. The damage may occur in as little time as 12 hours of pressure, but it might not be noticed until days later when the skin begins to break down. The skin is especially likely to develop pressure sores if it is exposed to rubbing (friction) and moving the skin in one direction and the body in another (shear), as in sliding down when the bed head is raised. Dampness (such as from perspiration or incontinence) makes the skin even more liable to develop pressure sores.

Who's At Risk?

People who cannot move themselves are at the greatest risk of getting bedsores, including people with:

- Spinal cord injury

- Paralysis

- Strokes

- Nerve (neurologic) disease

- Decreased mental awareness

Most bedsores occur in older people (over the age of 70), as the skin of older people may be thinner and may heal more slowly.

People in nursing homes and hospitalized people (particularly for hip fracture or intensive care) develop bedsores more commonly.

Smokers and people who do not get good nutrition (malnourished or undernourished), have incontinence (problems with bladder or bowel control), diabetes, or problems with blood flow (circulation) also have increased risk.

Signs & Symptoms

A bedsore appears first as a reddened area of skin, which then starts to break down to form an open, raw, oozing wound.

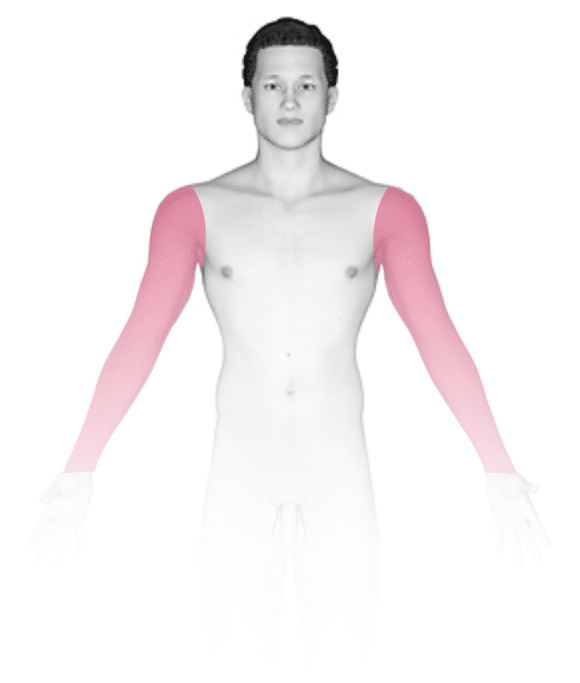

Bedsores occur at areas of abnormal pressure on the body:

- In a wheelchair, this is usually the tailbone (coccyx) or buttocks area, shoulder blades, spine, or backs of the arms or legs.

- In a bed, they may occur on the back of the head, ears, shoulder blades, hips, lower back, tailbone, or the backs or sides of the knees, elbows, ankles, or toes.

The pain level associated with bedsores depends on whether or not there is feeling in the area.

Bedsores occur in stages:

- Stage 1 has unbroken, but pink or ashen (in darker skin) discoloration with perhaps slight itch or tenderness.

- Stage 2 has red, swollen skin with a blister or open areas.

- Stage 3 has a crater-like ulcer extending deeper into the skin.

- Stage 4 extends to deep fat, muscle, or bone and may have a thick black scab (eschar).

Self-Care Guidelines

Do not attempt self-care for any ulcer beyond stage 2 in appearance.

In the early stages (1 and 2) of bedsores, the area may heal with relief of pressure and by applying care to the affected skin.

A good diet will aid skin healing, especially by taking in enough vitamin C and zinc, which are available as supplements.

For effective skin care:

- If the skin is not broken, gently wash the area with a mild soap and water.

- Clean open sores on the skin with salt water (saline, which can be made by boiling 1 quart of water with 1 teaspoon of salt for 5 minutes and kept cooled in a sterile container).

- Apply a thin layer of petroleum jelly (Vaseline®) and then cover with a soft gauze dressing.

- Be sure to keep urine and stool away from affected areas.

To relieve pressure:

- Change positions often (every 15 minutes in a chair and every 2 hours in a bed).

- Use special soft materials or supports (pads, cushions, and mattresses) to reduce pressure against the skin.

Treatments

In addition to self-care, your doctor might prescribe special pads or mattresses. Special dressings may be used, and whirlpool baths or surgery may be recommended to remove dead tissue. Infection requires antibiotic treatment. Sometimes deep wounds may require surgery to restore the tissue. Experimental work is now being done using honey preparations, high-pressure (hyperbaric) oxygen, and application of chemicals that stimulate cell growth (growth factors).

Visit Urgency

If a stage 2 bedsore does not begin to heal in a few days, or if the sore is at stage 3 or above, seek medical advice.

Get immediate care if you notice signs of infection (fever, spreading redness, swelling, or pus).

Trusted Links

References

Bolognia, Jean L., ed. Dermatology, pp.1645-1648. New York: Mosby, 2003.

Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. pp.1256, 1261-1263. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

Last modified on October 5th, 2022 at 7:50 pm

Not sure what to look for?

Try our new Rash and Skin Condition Finder