Lymphogranuloma Venereum (LGV)

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is an uncommon sexually transmitted disease caused by certain types of the bacteria called Chlamydia trachomatis. It is spread through having unprotected vaginal, oral, or anal sex. Lymphogranuloma venereum causes painful and swollen lymph nodes, which can then break down into large ulcers. The disease goes through 3 distinct stages as it develops. The first 2 stages of lymphogranuloma venereum may be minor, and you might not even be aware of any symptoms until you reach stage 3, called the genitoanorectal syndrome.

Who's At Risk?

Lymphogranuloma venereum has been found in people all over the world, but it is more commonly seen in tropical and subtropical countries. It is uncommon in the US and Europe, but, in recent years, more outbreaks have occurred in both areas, most often in white males who have sex with other men and who also are infected with HIV.

Lymphogranuloma venereum may affect any age and race and is probably equally common in men and women. However, men are often diagnosed in the earlier stages (probably because it is more visible) than women, who are often diagnosed in later stages, with complications. The peak ages are 15–40 years in the sexually active population. Anyone who has unprotected sex is at risk for lymphogranuloma venereum.

Signs & Symptoms

In the first stage of lymphogranuloma venereum, after a 3–30 day early development (incubation) period, a small painless bump or pus-filled lesion forms (on the penis, scrotum, vulva, or in the vagina) that may wear away to form an open sore (ulcer). This lesion often has no symptoms and heals without scarring within about a week.

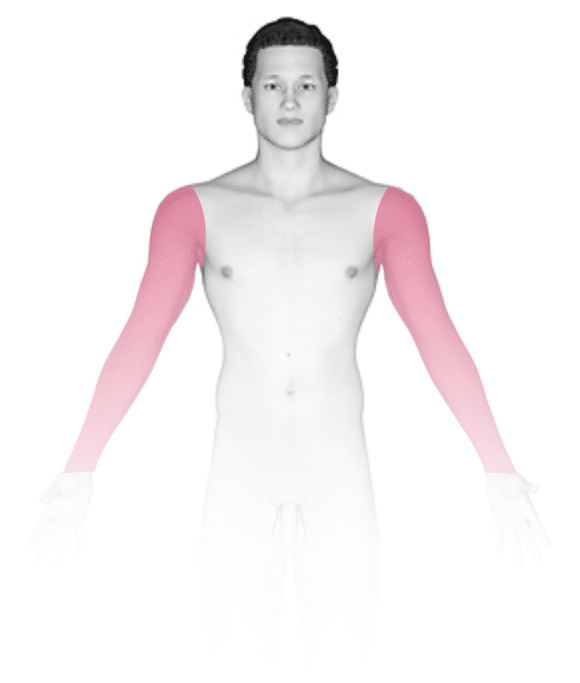

The second (inguinal) stage begins 2–6 weeks after the first lesion appears and consists of painful swelling of the groin or other lymph nodes. You may have symptoms of fever, chills, and fatigue. About one third of infected people develop a “groove sign” caused by pressure from the tight ligament separating the groin lymph nodes. These nodes join together to form “buboes,” which may split open and drain, or they may become hard and then slowly heal on their own. Women may not have any visible lymph node and have only mild back or belly pain. If the infection is in the anus, you may have blood or mucus coming out from the opening to the large intestine (rectum).

The third stage of disease is called the genitoanorectal syndrome. Particularly in women, this stage may be the first time symptoms are seen. Men and women who have been infected in the anus have rectal infection (proctocolitis), which can cause pain with defecation, deep boils (abscesses), and scarring. When infection is in the genital tract, the lymphatic system may be damaged, causing enormous swelling of the genitals as well as draining from scarred areas of the skin caused by deep tissue infection.

Self-Care Guidelines

- Do not attempt self-care if you suspect you might have lymphogranuloma venereum or if you have any sore or ulcer on the genital or rectal area. Avoid sexual intercourse, notify all sexual contacts, and see your doctor.

- To prevent lymphogranuloma venereum infection, avoid sexual activity, maintain a mutually monogamous long-term relationship with someone who is not infected, and use latex condoms consistently and correctly when engaging in sexual activity.

Treatments

- Blood and fluid culture tests may be done as well as testing for other sexually transmitted diseases, such as gonorrhea, syphilis, HIV, hepatitis, and chlamydia.

- People who have had sexual contact with anyone who has lymphogranuloma venereum within 60 days before the affected person had symptoms should be examined and tested.

- Antibiotics cure infection and prevent ongoing tissue damage, but they will not help to remove scars. Sometimes physicians will perform surgery to drain buboes or reduce the effect of scars.

Visit Urgency

If you suspect that you or a partner might have lymphogranuloma venereum or you have any sore or ulcer or a discharge from the genital or rectal area, avoid sexual intercourse, notify all sexual contacts, and see your doctor.

Trusted Links

References

Bolognia, Jean L., ed. Dermatology, pp.1290-1292. New York: Mosby, 2003.

Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed, pp.2198-2200. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

Last modified on October 10th, 2022 at 7:09 pm

Not sure what to look for?

Try our new Rash and Skin Condition Finder