Impetigo

Impetigo, a common skin infection in both infants and children, is caused by bacteria (Staphylococcus or Streptococcus) entering a cut or break in the skin. Although impetigo is usually a minor infection that can be easily treated, it could progress to more severe symptoms including deep skin infections (cellulitis), kidney inflammation, or meningitis. Impetigo can be further classified into 2 types: bullous and nonbullous.

- Nonbullous impetigo accounts for 70% of all cases and appears as tiny fluid-filled blisters that develop into honey–colored, crusty lesions. Generally they do not cause any pain or redness to the surrounding skin.

- Bullous impetigo is more common in infants and appears as larger, clear blisters filled with fluid. When these blisters rupture, they may leave a scale behind.

Who's At Risk?

Impetigo can occur in all age groups but is more commonly seen in school-aged children and infants. Look for a sore that develops into a honey-colored crust. Bullous impetigo is more commonly seen in infants and usually develops on the face, buttocks, and diaper area. Infants are at a greater risk for these infections because their immune systems are not fully developed. Other risk factors may include insect bites (that may be scratched) or poor skin cleansing. Impetigo can also be spread by touching a contaminated object (fomite). It is spread rapidly through day-care centers and nurseries.

Signs & Symptoms

There are 2 common forms of impetigo: impetigo with blisters and impetigo without blisters (fluid-filled bubbles on the skin surface).

Non-blistering impetigo:

- Tiny pimples or red areas quickly turn into oozing, honey-colored, crusted patches (usually less than an inch) that spread.

- The face or injured (traumatized) areas of the skin are affected.

- There may be some itching or swollen lymph nodes, but the child feels generally well.

- Sometimes deeper, pus-filled sores and scabs that leave scars occur.

Blistering impetigo:

- Painless blisters (about an inch or less) occur that may break easily.

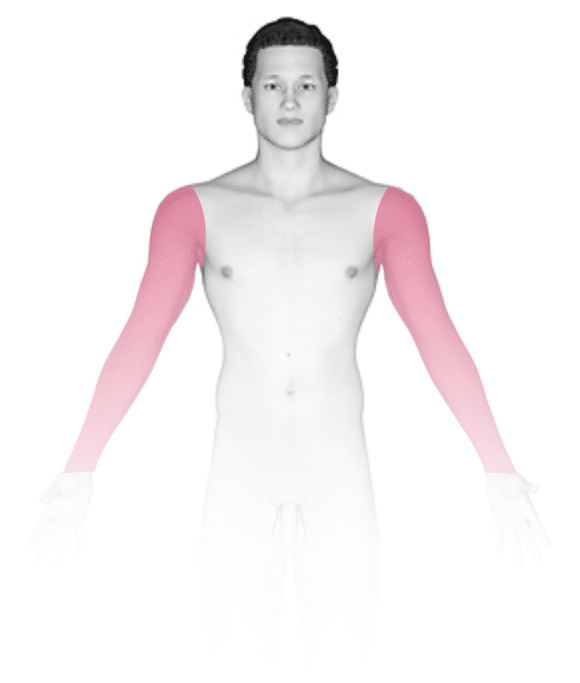

- These often spread to the face, trunk, arms, or legs.

- The person feels generally well.

The infection associated with impetigo may be:

- Mild – Only a few of either type of lesion over a small area of skin, and the child feels well otherwise.

- Moderate – Over 10 lesions, and several small skin areas are affected.

- Severe – Many lesions; large areas of skin are affected; and/or the child feels ill, with fever, diarrhea, or weakness.

Self-Care Guidelines

Prevention of impetigo:

- Keep the skin clean with soap and water.

- Treat cuts, scrapes, and insect bites by cleaning with soap and water and covering the area if possible.

For mild infections:

- Gently wash the area with a mild soap and water twice or more daily and cover with gauze or a non-stick dressing if possible.

- Apply an over-the-counter antibiotic ointment after washing the skin 3–4 times daily. Wash hands after application or wear gloves to apply.

- To remove crusts, soak with a vinegar solution (1 tablespoon of white vinegar to a pint of water) for 15–20 minutes.

- Wash clothing, towels, and bedding daily, and don’t share these personal items with others.

- Wash hands frequently, try not to touch the affected areas, and keep fingernails cut.

- Keep your child home until scabs or open areas have healed.

Treatments

In addition to measures for mild impetigo already mentioned, the doctor may prescribe:

- Topical antibiotics (usually mupirocin)

- Oral antibiotics (cephalosporins, amoxicillin, cloxacillin, dicloxacillin, erythromycin, or clindamycin)

If your child’s doctor prescribes antibiotics, be sure the child takes the full course.

Visit Urgency

See your child’s doctor for any infection that does not improve. See the doctor immediately for moderate to severe infection or if your child has a fever or severe pain.

If your child is currently being treated for a skin infection that has not improved after 2–3 days of antibiotics, return to the child’s doctor.

Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) is a strain of “staph” bacteria resistant to antibiotics in the penicillin family, which have been the cornerstone of antibiotic therapy for staph and skin infections for decades. CA-MRSA previously infected only small segments of the population, such as health care workers and persons using injection drugs. However, CA-MRSA is now a common cause of skin infections in the general population. While CA-MRSA bacteria are resistant to penicillin and penicillin-related antibiotics, most staph infections with CA-MRSA can be easily treated by health care practitioners using local skin care and commonly available non-penicillin-family antibiotics. Rarely, CA-MRSA can cause serious skin and soft tissue (deeper) infections. Staph infections typically start as small red bumps or pus-filled bumps, which can rapidly turn into deep, painful sores. If you see a red bump or pus-filled bump on your child’s skin that is worsening or showing any signs of infection (ie, the area becomes increasingly painful, red, or swollen), see the child’s doctor right away. Many people believe incorrectly that these bumps are the result of a spider bite when they arrive at the doctor’s office. Your doctor may need to test (culture) infected skin for MRSA before starting antibiotics. If your child has a skin problem that resembles a CA-MRSA infection or a culture that is positive for MRSA, the doctor may need to provide local skin care and prescribe oral antibiotics. To prevent spread of infection to others, infected wounds, hands, and other exposed body areas should be kept clean and wounds should be covered during therapy.

References

Bolognia, Jean L., ed. Dermatology, pp.1117-1118. New York: Mosby, 2003.

Freedberg, Irwin M., ed. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed, pp.1394, 1845, 1848, 1857-1869. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

Last modified on August 16th, 2022 at 2:45 pm

Not sure what to look for?

Try our new Rash and Skin Condition Finder